This is the third issue concerned with the origin of languages. The last issue (hyperlink) addressed the first point regarding the evolutionary model’s assumptions:

1. Change in grammar has been in the direction of increasing complexity.

We demonstrated that languages are in fact simplifying with time. Second point:

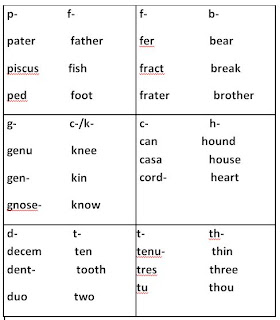

2. Sound shifts are random in the evolutionary model. However during the first millennium, B.C., a very significant change called the First Germanic Sound Shift occurred in consonants when Proto-Germanic was developing. The pattern of consonant changes:

Then from 600 to 800 A.D., the Second Germanic Sound Shift occurred, again demonstrating consistency in the patterns.

These examples demonstrate that languages shift sounds in non-random patterns. Third point:

3. Languages change uniformly through time according to the evolutionary model:

Here is Matthew 6:24 in three time periods. The first is Old English from 1,000 years ago:

Ne mæg nan man twam hlafordum ƥeowian oððe he soðlice ænne hatað and oðerne lufaƥ: oððe he bið anum gehyrsum. and oðrum ungehyrsum; Ne magnon ge gode ƥeowian and woruldwelan:

Matthew 6:24 from 500 years ago:

No man can serve two masters. For ether he shall hate the one and love the other: or els he shall lene to the one and despise the other: ye can not serve God and mammon.

Matthew 6:24 from 37 years ago:

No one can serve two masters. Either he will hate the one and love the other, or he will be devoted to the one and despise the other. You cannot serve both God and Money.

Notice the phenomenal amount of change in the 500 years between the first two, but only minimal change in the last 500 years. This is not a uniform rate of change. Next point:

4. Change in language occurs in isolation:

The evolutionary biological model needs small, isolated gene pools for a new trait to become established. However people groups that remain isolated preserve their language with minimal change. History shows when peoples speaking different languages come into contact with each other, rapid changes occur. Vocabulary is borrowed in both directions, and grammar is simplified while efforts are made to establish communication. Think about what you do with a person who speaks no languages you speak: Me Tarzan – you Jane. Final point:

5. The biological model calls for random chance mutations in the four letters of the DNA alphabet to add information—vocabulary:

In our language analogy, new words would appear by random changes of syllables. But when we look at vocabularies, new words are formed by:

1. Logical additions to or combinations of existing words:

Verb – to mother

Adjective – motherless, mothering, mother’s

Adverb –motherly

Noun – mother, motherhood, mother-in-law, motherboard, mother-of-pearl, mothercraft, motherland, Mom, Mommie.

2. By borrowing from other languages:

Kimono, kindergarten, babushka, taco, monsoon, wadi, sitar, igloo, wampum.

3. Or by creating acronyms:

NASA, NATO, laser, scuba, radar, snafu, Gestapo (a borrowed acronym).

From these examples it should be clear that vocabulary grows through intelligent input with a plan.

In summary, the evolutionary biological model fails when applied to languages. The historical account in Genesis Chapter 11 explains the supernatural origin of unrelated language family trees. Languages have been simplifying their grammar; vocabulary has been added by intelligent input. Rapid change occurs when languages come in contact with each other.

The next issue will discuss the parts of the body relating to language.